Definition

Spatially and geographically defined, marine or coastal areas in which specific management measures are applied to sustain important species [fisheries resources] during critical stages of their life cycle, for their sustainable use (UNEP, 2005)

Refugia Concept

- NOT be “no take zones”, ·

- Have the objective of sustainable use for the benefit of present and future generations·

- Provide for some areas within refugia to be permanently closed due to their critical importance [essential contribution] to the life cycle of a species or group of species·

- Focus on areas of critical importance in the life cycle of fished species, including spawning, and nursery grounds, or areas of habitat required for the maintenance of bloodstock

- Have different characteristics according to their purposes and the species or species groups for which they are established and within which different management measures will apply·

- Have management plans

Summary

The Department of Fisheries Malaysia has identified tiger prawn at Kuala Baram and the mud spiny lobster on the east coast of Johor that needed intervention in order to secure the sustainability of the fisheries resources. The Department has developed a management plan for both the fisheries refugium to ensure the sustainability of the fisheries resources.

The refugia on the east coast of Johor and Kuala Baram cover an area of 17,784 km2 and 852 km2, respectively. The refugia approach is not an extension of the no-take zone. It is a set of specific actions specifically crafted to protect the targeted species. In the case of the mud spiny lobster, the DOFM takes three key steps,

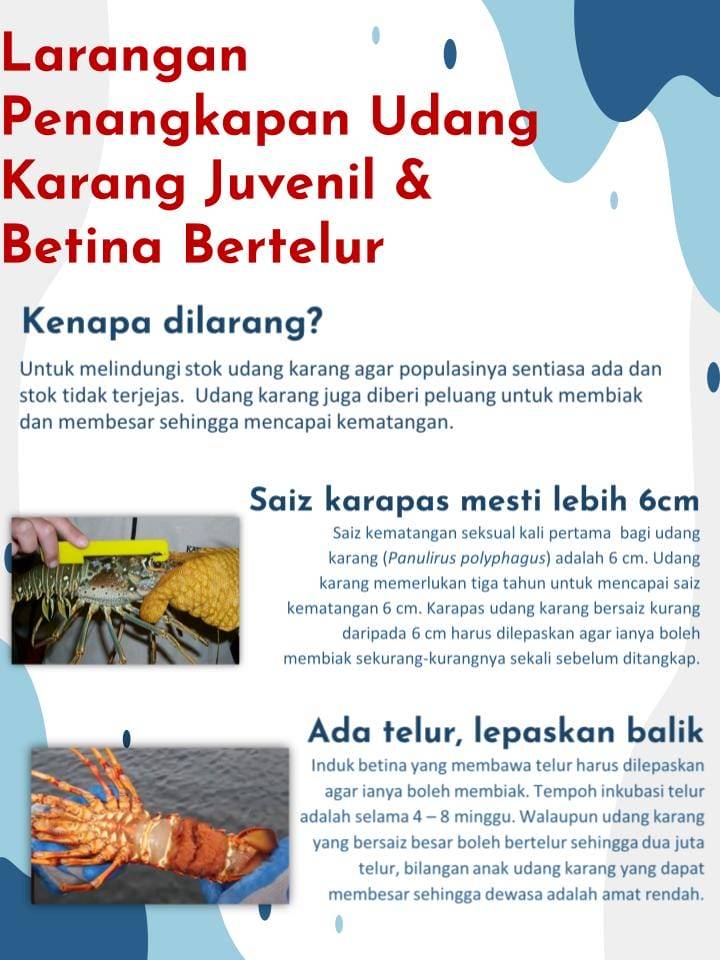

- No-take of juvenile lobster (carapace length <6 cm),

- No-take of berried female

- Close fishing season in the sensitive area is crucial for spawning in the refugium from December until the last day of February in the coming year.

In addition, constructing artificial reefs to increase habitats for the adult lobster has been recognized as an aid to sustain the lobster population in the refugium.

While the refugium for the tiger prawn is subdivided into two areas, Area A covers the nursery ground in the coastal area. In contrast, area B covers the spawning ground located in a deeper area up to 50 m water depth. Area B extends from the shore up to 12 nautical miles.

Tow trawlers are prohibited in area B from August to October yearly. Besides, the Department will implement size and weight limitations for the tiger prawn in the fish landing jetty. Artisanal fishers are encouraged to harvest Tiger prawns exceeding the total length of 30 cm and body weight exceeding 90 g. Concurrently, a scheduled restocking will be conducted to ensure continuous larvae existence in the refugium.

The Department realizes the importance of stakeholders’ engagement in co-managing the fisheries refugia. DOFM has established the National Fisheries Refugia Management Committee (NFRM). The NFRM will be advised and guided by the National Scientific and Technical Committee (NSTC) regarding the scientific and technical aspects.

Most importantly, the site management committee is the refugium program’s key driver in implementing the management plans. The site management committee is represented by fishers, government agencies, local councils, researchers, and industrial players in the supply and demand chains.

DOFM recognized the significance of financial sustainability in the implementation of fisheries refugia. Several strategies have been outlined to raise funding to support the execution of the management plan which includes the establishment of National Trust Fund for Refugia and exploring new potential of funding from various conservation organizations.

DOFM has drawn a five-year plan for the fisheries refugia; the program’s performance will be evaluated annually and revised from time to time. With a proper management framework, support and endorsement from stakeholders, and guidance from SEAFDEC, UNEP, and GEF, the fisheries refugia shall contribute to sustainable fisheries, particularly the small-scale fishers, in protecting the fisheries resources, as well as improve the social economic status of the artisanal fishers.

Limiting fishing activity may not be enough to achieve sustainable fishery exploitation due to a non-linear relationship between the animal size and egg production. However, catch restriction of animal of particular size and life stages may potentially maintain the population

Pauly (1997)

Refugia Team

Our team of experts ..

Datuk Haji Mohd Sufian Bin Sulaiman

Ketua Pengarah Perikananan Malaysia

En Bohari Bin Haji Leng

Pengarah Kanan Bahagian Konservasi Dan Perlindungan Perikanan

Pn. Liza Binti Long

Timbalan Pengarah Jabatan Perikanan Laut Sarawak

En. Jamil Bin Musel

Pengarah Institut Penyelidikan Perikanan (FRI) Bintawa

Pn. Nurridan Binti Abd Han

Pegawai Penyelidik Kanan Institut Penyelidikan Perikanan (FRI) Bintawa

En. Rizwan Bin Nordin

Ketua Wilayah III Pejabat Perikanan Laut Wilayah III Miri

En Sallehudin Bin Jamon

Pengarah Institut Penyelidikan Perikanan (FRI) Kg Acheh

En Abd Haris Hilmi Bin Ahmad Arshad

Pengarah Institut Sumber Marin Asia Tenggara

En. Ryon Siow

Pegawai Penyelidik Kanan Institut Penyelidikan Perikanan (FRI) Kg. Acheh

Pn. Nur Afifah Binti A. Rahman

Pegawai Perikanan Pejabat Perikanan Negeri Johor

Cik. Nur Hidayah Binti Asgnari

Pengawai Penyelidik Institut Penyelidikan Perikanan (FRI) Kg. Acheh

Pn. Norhanida Binti Daud

Penyelidik Kanan Institut Penyelidikan Perikanan (FRI) Batu Maung

Pn. Rozita Hani Binti Safiei

Pembantu Penyelidik Institut Penyelidikan Perikanan (FRI) Batu Maung

Pn. Rosmawati Binti Ghazali

Ketua Cawangan Pengurusan Taman Laut Dan Perlindungan Marin

Pn. Nurashiqin Binti Sallih Udin

Pegawai Perikanan Cawangan Pengurusan Taman Laut Dan Perlindungan Marin

Pn. Nor Khalilah Binti Zainuddin

Pegawai Perikanan Cawangan Pengurusan Taman Laut Dan Perlindungan Marin

Pn. Asma Binti Md Soh

Pembantu Perikanan Cawangan Pengurusan Taman Laut Dan Perlindungan Marin

Pn. Nor Amnah Binti Taib

Penolong Pegawai Perikanan Cawangan Pengurusan Taman Laut Dan Perlindungan Marin

Spiny Lobster Refugia Site

Map showing the location of the spiny lobster refugia site, covering an area of approximately 1,717 km2 at East Johor, Peninsular Malaysia

Tiger Prawn Refugia Site

Map showing the location of the tiger prawn refugia site, covering an area of approximately 852 km2 in Kuala Baram area, Miri, Sarawak

Landing Size Restriction

Measuring Equipment

Panduan Mengukur Panjang Karapas Udang Karang

Guide to Measure Carapace Length of Spiny Lobster

Proposed Area Tiger Prawns

Proposed Closed Season

MYREP2017Q301 Stakeholder Consultation Kuala Baram Miri 20180717

MYREP2017Q302 Stakeholder Consultation Tanjung Leman Johor 20170817

Pelan Pengurusan Refugia Perikanan Bagi Udang Karang Di Kawasan Pesisir Pantai Timur Johor

Fisheries Refugia Management Plan For Mud Spiny Lobster On The East Coast of Johor

National Scientific And Technical Committee Meeting

Refugia Lobster Brochure

Refugia – Spiny Lobster Research 2022

Refugia – Spiny Lobster Information Center 2022

Refugia – Spiny Lobster Consultation 2022

Refugia – Tiger Prawn Research Activity 2022

Refugia – Tiger Prawn Information Center Activity 2022

Refugia – Tiger Prawn Consultation Activity 2022

Refugia – Galeri Udang Kara